Let No One Sit On the Sidelines

It’s easy to put on gear, lace up the shoes and grab a ball- but for some, it is not that simple. Not only do they have to prepare for the game, but they also grab something most don’t: a wheelchair.

Many students are used to “regular” or ambulatory sports, where running and walking is the main focus of moving down and up the court, field or track. What they are not used to are the sports that eliminate a crucial part of their body used in sports: their legs. Over ten percent of the population has a physical disability resulting in the inability to play sports. GLASA, The Great Lakes Adaptive Sports Association, keeps kids and adults alike from sitting and watching from the sidelines and gives them a chance to play. Sophomore Drew Higgins, who has been diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy, a condition which affects his motor skills, joined GLASA in hopes of being like all his friends who played sports.

“I wanted to play sports like my friends,” Higgins said. “GLASA gave me a chance to be like everyone else.”

Cindy Housner founded The Great Lakes Adaptive Sports Association back in 1999, with their motto being “let no one sit on the sidelines.” They started with less than a dozen participants in hopes of raising awareness and providing a program for those who could not play ambulatory sports. Now, GLASA has impacted over 3,000 youth and adults within the Illinois-Wisconsin area each year through sports education and outreach programs. They offer 25 different sports each year, including some of Antioch’s favorites, but adapted. Swimming, wheelchair football, wheelchair basketball, tennis, track and field, sled hockey and powerlifting are some of the most popular among GLASA athletes. Alec Tranel, a multisport GLASA alumni and coach, shares his love of the sport and the organization.

“There are more disabled sports than there are regular sports,” Tranel said. “Meaning if you look at the ranges of disabilities there are, we as the GLASA program are allowed the opportunity to provide a sport for them.”

The Chair:

The key difference to adaptive sports is the equipment itself. Athletes use a sports chair, rather than a wheelchair one uses for personal use. The two big wheels are cambered, or at an angle. This allows the player to move faster on the court and it guards their hands from being smashed when playing defense. Also, there are three to five different casters, or little wheels surrounding the two big ones. There are two casters in the front for movement and the anti-tip wheel in the back. Just like the name says, it allows one to push to move or bump into other players without falling backwards.

The Game:

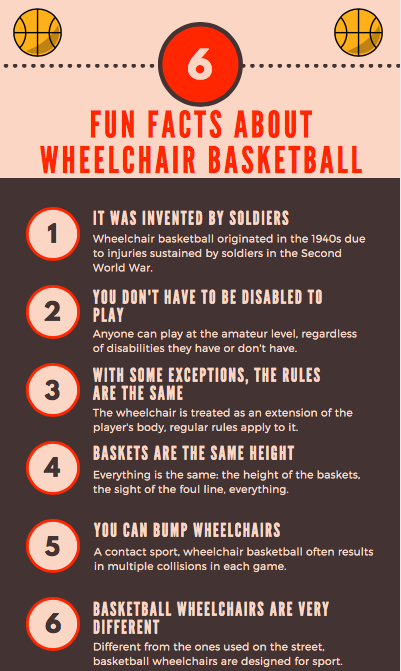

GLASA’s wheelchair basketball program is just like the sport played at the competitive level. The main difference in adaptive and ambulatory basketball is that for every two pushes, there has to be one dribble. A player can dribble in whichever way is comfortable, as long as the ball makes contact with the ground.

“I like to stop my chair and then dribble,” Higgins said. “It is easier for me to control the ball and my chair. Others continue down the court and put a backspin on the ball to keep the momentum. It is just a matter of preference.”

While offense rules generally are the same, defensive players have to pay attention to their wheels, as the chair is considered a part of their bodies. To set a block, or a pick, the players have to be perpendicular to the other player, using their larger wheels instead of the casters.

Adaptive sports are definitely not as common as ambulatory sports, but should be appreciated as the same. Many people believe that because there is no running involved, it is deemed as easy. But, this is not the case. A player uses different muscles in the chair than running down the court, resulting in a different feeling and style to gameplay. All in all, there is an art to both styles of the game.

“The ball handling and dribbling is the main visual difference other [ambulatory] players see,” Tranel said. “The game itself does have a slower pace, but this allows more strategic maneuvers. One of the beauties of watching wheelchair basketball, especially if you understand the rules and how players maneuver, you can see the different abilities and the behind the scenes of the strategy behind making a basket.”

GLASA is always in need of volunteers for their practices, sporting events and special programs. Students can show up to any sporting event and help the coaches and the players learn and grow as an athlete. No previous knowledge of the sport is required. By chasing balls, setting up equipment and sometimes getting into a sports chair and playing games and doing drills can benefit the team in more ways than one.

“The best way to introduce people to disability awareness is being able to show them what we can do,” Tranel said.

In need of NHS Hours? Just want to donate time? If you are interested in learning more about volunteer opportunities, fill out the Volunteer Profile Form and Waiver at www.glasa.org and send it to GLASA’s Program Director & Volunteer Coordinator, Micaela Fedyniak, at [email protected].